Change management might seem like a daunting, complex subject, but it can be a real adventure and a very informative one. I’m going to pass on to you some first-hand insight and knowledge that I’ve gained from my own adventures.

Here’s a breakdown of my talking points:

- Why talk about change management?

- Product development lifecycle

- The Cynefin framework

- Storytime: anecdotal insight

- Tips and tricks from my experience

About me

I work at Farfetch as a product operations principal. Before that, I was working at ThoughtWorks, and also Sky TV. Throughout my career, there's been one major tenet: I want to help product teams to make better products.

For me, there are three major focuses: process efficiency, capability, and team happiness. With this subject, it’s impossible to have one major focus, it’s a holistic process.

So, to get started, let’s strip this subject down to its core. 👇

Why talk about change management?

Well, as you're probably aware, there’s a lot of crossover between product operations and change management. And we are kind of ideally placed in the organization to be thinking about how change happens.

How vs what

We should be challenging our product development teams to focus cross-functionally on what they’re focused on and how they’re focusing on it. The ‘what’ really encompasses the following:

- Customer goals

- Solution ideas

- Alignment to strategy

- The broader goals of the business

When looking at the ‘how,’ we want to focus on the following:

- How do our teams operate?

- How do we instill a culture of collaboration without forcing change?

- Coach people on how to instill change and help them through that.

The key takeaway to this last point is that you can’t just be beavering away in a room focusing on new processes, and then roll them out and expect everyone to adopt them. Everyone across the team needs to be in on each part of the development lifecycle. It’s about a culture of collaboration.

Product development lifecycle

It can be pretty draining, but product operations are well-placed to look across at the whole product development lifecycle, at all the various actors, players and cross-functional teams that are in this space.

What change actually means and why it’s important?

If you’ve ever been through any kind of change in your organization, whether you've been an implementer of it, or if the change is happening to you or with you, it can often feel incredibly uncomfortable. That's totally normal, change is a constant and natural part of all our lives.

The problem is that people feel like they’ve lost control through change. I believe that product operations are ideally placed to ensure people don’t feel that change is a total loss of control. This is important, because the fact is, change is going to happen whether you’re ready for it or not. Because…

Organizations have to grow

This is kind of the essence of change, right? If you ever worked in any organizations that are scaling, what you'll realize is that organizations are always growing.

They have to grow because if they aren't growing, they're almost certainly shrinking. A shrinking business disappears. The lesson to take from this is that change is certain, and if you don’t take control of it it’s going to be for the worse rather than for the better.

Now, the scale and pace of growth is going to vary across organizations. But one thing is for certain, big organizations do not tread water. They are not in a stable situation, and they never will be.

The Cynefin framework

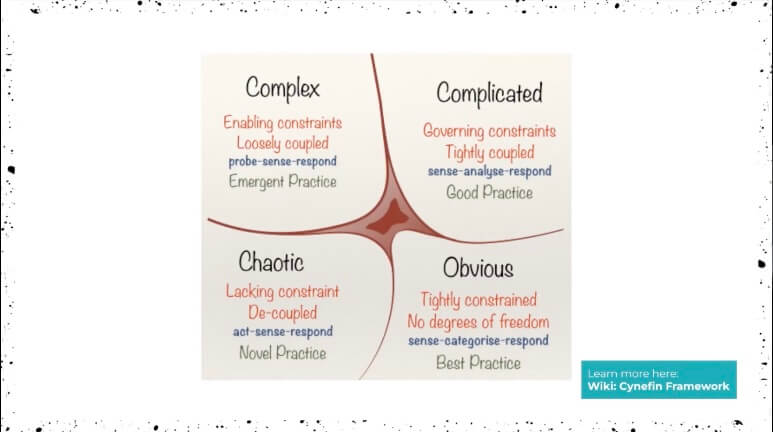

The truth is, we should be preparing for the worst, for the chaotic times. The Cynefin framework can be really useful to refer to, and it can give us a good reference point for the kinds of changes we have to prepare for.

The obvious space

This is where things are generally best practice. That doesn’t mean that there isn’t change in that space; we just might be looking at minor process improvement, documentation standards, for example. This is the most stable space. We can prepare for that and plan for that appropriately.

The complicated space

Take an organization, for example, that's been using design sprints for a while, this is quite complex because there's a number of people involved and the problems they tackle are quite challenging. It’s generally a good practice. And we might want to improve on our practices slightly, to alter our focus slightly.

Complex and chaotic space

To be clear, chaos is not an inherently bad terminology here. Again, this is something that just happens, and we have to be prepared for it. This is where emergent and novel practices are appearing. Imagine someone picks up a new tool and starts to use it, hat’s an emerging practice.

If, on the other hand, someone is using existing frameworks and tools and doing something completely revolutionary with them, you might be entering into chaotic space.

Eventually what happens is that the novel practices become slightly more emergent. More teams start to pick them up, and we start to make decisions over whether those things should be good practice.

Finding the best practice

Eventually, over a set period, these things become best practice and become slightly more obvious. But the important thing to note is that this best practice scenario is never going to be constant. Practices will start to be evolved and adapted and that’s when the novel practice re-emerges.

Storytime: anecdotal insight

I want to tell you about this time the product design director came to our small product operations team. As I mentioned earlier, product operations looks at the whole product development lifecycle. Now, obviously, there’s a crossover between product development and product design. There's a collaboration between these different functions.

The design director came to me and said, “we’re producing high-quality design work, and we're going to the spec of what the product manager has devised for us. I don't believe that our designers are fully aware of the kind of customer value that they're adding.”

His objective was to make it easier for those individual product designers working with product teams to be able to showcase the value of their greater customer-centricity.

Questions arising

Questions that arose from this situation were: How do we talk about the work that we're doing? How do we know that the business goal is the customer goal? When do we know when to stop and launch an experiment?

The impact of this was beyond product design but started in that space. There’s a number of things that were introduced as part of this.

Design rituals

We have much clearer design rituals for:

- When we start planning work.

- When we review work.

- When we look back introspectively on the path of continuous improvement.

Starting conditions

We had to establish what long term goals we were setting right from the outset and to do that, we had to develop some very targeted, pointed questions:

- What is the business goal?

- What is the customer goal?

- What do we intend there?

- What metrics will show success?

- What is the timeline that we're working with?

Those questions were asked really upfront. This is essential because you can’t form the right strategies unless you’re asking the right questions.

We were doing good design work. But what does good mean? And if we don't understand what the customers are looking for, or even when to stop doing this work, we can’t move on to the next thing. That's why we introduced….

Definitions of done

We had to be certain of what the minimum amount of design work was to achieve the goal. Should we launch something? Or should we work a bit longer and create an even better experience? This is all about establishing how we know when we’ve accomplished a goal. What are the metrics that determine this?

It’s all well and good to have goals, but if you don’t know when to move on to the next thing, you might as well not have goals at all.

Complexity levels

It’s important to talk about the various types of work that we do. This can help with our design estimation. And it’s especially important when teams are trying to sync up. The product team might think that something is a relatively quick and easy thing to do, but the design team might come in and say that it’s going to take a really long time.

Introducing complexity levels opens up that conversation and allows it to happen.

Introducing standard agile practice

These have to be established with a working progress limit. Designers have to be focused on what the intention behind the work is. If a work is particularly complex, then maybe it’s best to focus on one thing at a time. If a piece of work is relatively obvious, then you might be able to pick up one or two different things at the time.

How we scaled

I’m going to use this section to demonstrate how we were able to scale using these methods and approaches. There were many different aspects that we were able to grow.

- 5 customer verticals. We're in a different organizational structure now, but back when we did this, we had 5 different verticals.

- 60 product design and research people. This was on all different levels, from junior to director.

- 50 product management and leadership level people, from associate to VP level. That was the immediate effect. The product design and research section was where the biggest impact of change was going to be felt. Because of their close collaboration with product management, they were going to feel the change and have to be involved in all of that change.

The wider impact

The wider impact of this was that around 250 of our engineering partners, our platform partners, and eventually our business partners, felt the effects of this change. But they might not have been directly involved in it.

This process took a long time. After around nine months, we realized that there were a number of these changes that hadn't taken place, even though we had planned as best as we thought.

Tips and tricks from my experiences

Setting up for success

Having something to fall back on gives you a really strong foundation when things inevitably go wrong. When things don't go as you prepared or planned, you still have to be able to move forward with strength and hopefully be successful.

Understand the current state

You have to understand exactly the situation that your team and your organization as a whole is in. When I first came in at Farfetch, the current state had been researched, but I had to do that research myself. This research focused on the organization's broader goals but also focused on how the team functions.

That way I had a benchmark for success after 6 months of being there.

When coming into any role like that, it’s important to get the big picture. Build up relationships with everyone, even those that you’re not likely to have much to do with. If you can build up a strong, holistic vision of the company, if you can build up a consensus, we can be fully aligned in our strategy going forward.

Build relationships

This was maybe my biggest mistake in this process. I failed to build up a solid relationship before making the change. Building good relationships is absolutely essential for building your organization’s vision of what you’re trying to achieve. Your vision has to be unified behind a common consensus.

Having no vision causes a lot of confusion.

Familiarity bias overcomes a lot of complexity

With a lot of processes and systems that are overly complex and specific to individuals, people have to be confident that the strategies they're following are the right route to go down. Being familiar with those complex processes will help the team deal with even the most complex procedures.

Plan to celebrate success

There's a balance to be struck between celebrating absolutely everything and only celebrating big things. Focus on celebrating the things that truly have value. Teams have to be confident that they’re making progress and that the work they’re doing actually has value.

If teams don’t feel this, they’re going to become demotivated pretty quickly.

Communication is key

A big part of keeping your team motivated stems from leaders being able to effectively communicate. This links in with the last point. If leaders aren’t communicating success as well as failures, teams are going to lose faith in their goals and start to feel that their work is purposeless.

Identifying broken links potentially ahead of time

One of the biggest enemies to productivity in any workplace is breakdowns in communication. The important thing is to notice this ahead of time. Let’s say one of your team, for example, is on long-term sick leave, or let’s say one of them is on maternity leave, the latter you can plan for ahead of time.

If you can put a contingency plan in place ahead of time you can prevent mistakes from happening and maintain productivity.

Have strong documentation

I was able to articulate what we are doing to get everyone on board. Do you have data, metrics, and case studies to back up what you are doing? Maybe you do, but unless you have this collated in one place, it might be hard to unite everyone behind what you’re doing.

Can you prove the value of what you’re doing? If not, it’s going to be hard for anyone to have faith in your methods and approaches.

To wrap up: silence can be corrosive

If you're not hearing feedback, it's incredibly challenging to know what's working and what's not working. By effectively creating a culture of collaboration that your team has confidence in, you're going to know what’s going wrong as it’s happening.

If little things are breaking down here and there, but no one’s talking about it, it might not seem like a big thing at first. But as your ship continues to fill with little holes, pretty soon it’s going to sink.

You can’t do it alone

I’ll be honest, I tried to make this happen by myself because of our small team, but it simply isn’t ever the case. Your job is to bring about a team of people with individual talents to bring about change. This is not an ego trip, we’re here to solve problems.

And with something as complicated as change management, you simply can’t go about it alone. You need an army of people at your side. Let’s do it together!

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn