Learning to navigate an uncertain world

I get asked about the “product mindset” a lot in my role as Head of Product Operations at Cognizant. My clients are looking to build the right thing for themselves and their customers. They rightfully see the product mindset as a way to enable that.

However, I get questions like:

- What is “it?”

- Can we do “it” in three months?

- Can we do “it” without changing the org?

- Can we do “it” without causing too many disruptions?

The reason is that the product mindset is a bigger shift than most people realize from the way that today’s orgs work. The current worldview of the product mindset is that if you just think (smartly) about something enough, you will figure it all out and be successful. If you don’t do this, you will fail. That is why we need to have everyone thinking through things as much as possible with their superior product sense.

Unfortunately, this just isn’t true. No amount of thinking (smart or otherwise) will figure everything out before it happens. Especially when you are building something new, as most product people are.

In this post, I’ll tell you why this isn’t a simple functional mindset or even a refocus on outcomes over output.

Training product mindset

I train lots of people inside and outside of Cognizant in the product mindset. I’ve focused this training on a very simple but powerful action: asking “why” more.

It starts with a discussion of the “5 whys” from the Toyota Production System. And moves into a case study for a hypothetical banking client where I ask everyone to think of questions they would ask in a particular situation.

The reason I ask salespeople, engineering managers, architects, and others to ask “why” more is that if you can ask more of the right questions you will understand something about the true outcomes your clients are trying to get at.

This is a great start and can improve any practice. However, there is something very core about the way you consider the world you are building for. Under the surface of asking “why” there is a lesson about how you make assumptions about people and the future.

The Idea Maze

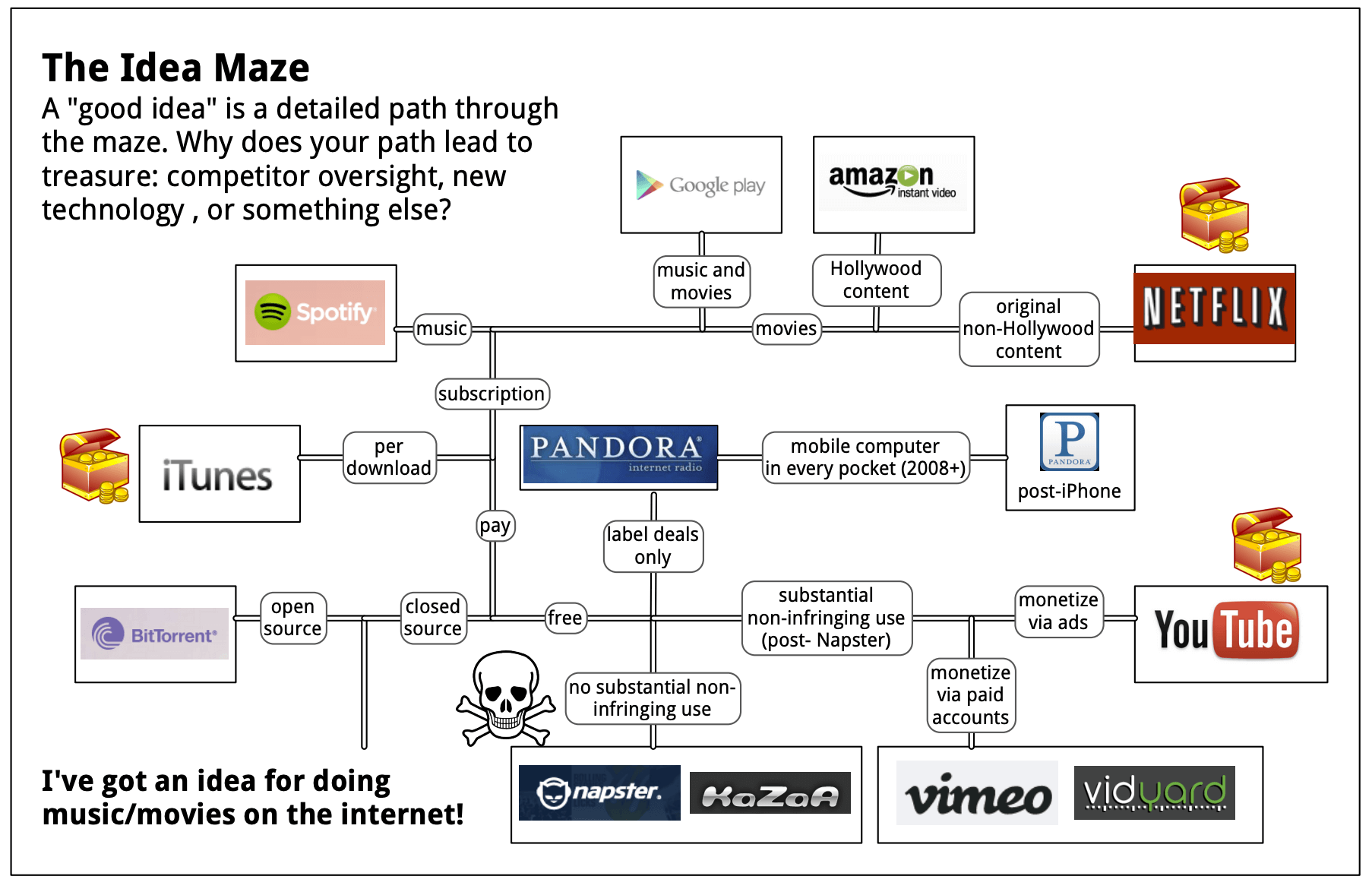

The Idea Maze is a concept from a 2013 paper "Market Research, Wireframing, and Design" by Balaji S. Srinivasan. This paper is used as an important concept by various product thinkers like Chris Dixon, Benedict Evans, and others.

The Idea Maze is how you go through a set of decision points to get to a successful business. Netflix is often cited as a series of decisions that were needed before you could get their successful model (at least the one in 2013).

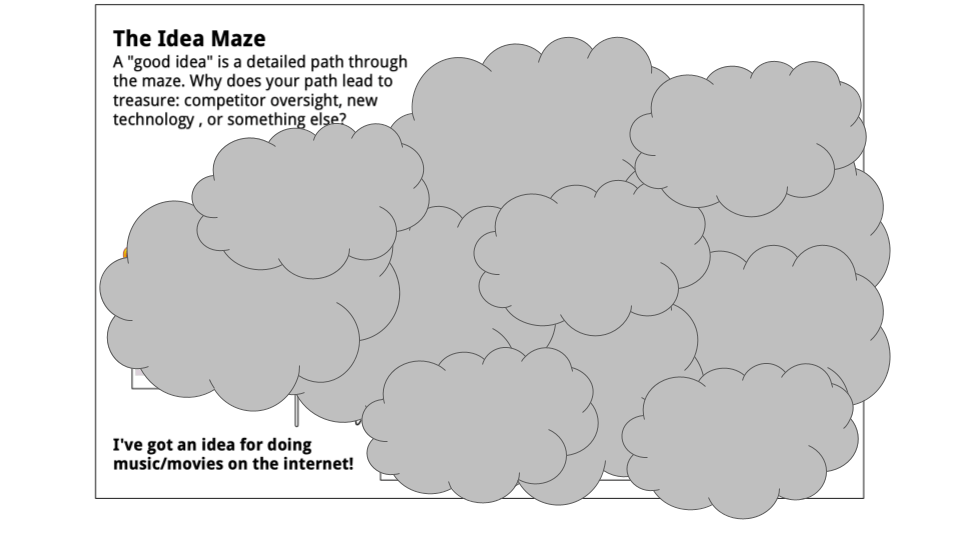

What the Idea Maze looks like when you are getting started on something new, which most product people are building, is more like this:

What’s missing is that you don’t actually know what’s beyond your current idea or decision. You need to go find out through research, prototyping, building, experimentation, etc. Balaji discusses the fact that a prototype is not the same as actual execution but doesn’t note the fact that the maze is often unknown ahead of time. This is related to another concept that is referred to as “deception.”

The Idea Maze vs. Deception

A book I recommend to a lot of people is “Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned” by Kenneth Stanley and Joel Lehman. It’s a series of papers in the machine learning domain but ends up having a lot of product-related lessons. It’s a top 10 product thinking book I recommend.

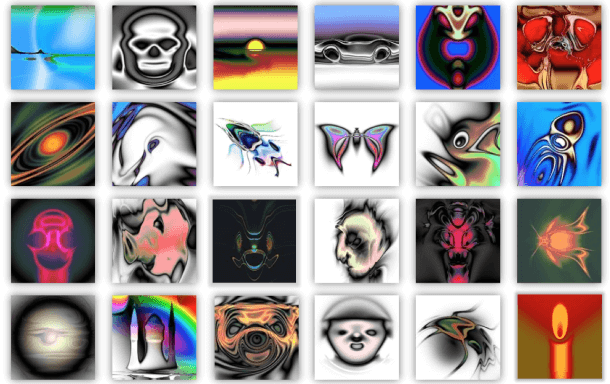

The main topic in this book is an experiment called PicBreeder. It is a site that uses genetic algorithms to create images like the ones below. They started off very simple and with little color. They evolved through humans saying which one of a set of images they liked most. Through thousands of generations, PicBreeder got to some of the great images like the butterfly and skull. People didn’t think that they would get to these great images though they were only seeing each image set that they would then choose the winner.

Stanley and Lehman take this to the case of vacuum tubes eventually leading to computers. Or bacterial life on earth leading to humans. There was no plan to get from these very early stages to higher-level capabilities.

They state that this is like trying to cross a lake using stones:

The reality is that it looks like this:

You can’t see how to cross the lake or even what “crossing the lake” would mean as an end goal most of the time. Stanley and Lehman say this about objectives:

“This situation, when the objective function is a false compass, is called deception, which is a fundamental problem in search.”

In my product day-to-day, I’m confronted with many different people that are incredibly certain that we are moving the right way towards the best objective. Product sense and taste is tied up in this when people say someone is good at “doing” product. The product mindset isn’t about this certainty. The reason why we ask “why” so much is because this certainty is probably wrong.

The fundamental problem

Without the product mindset you would believe so much about the world that would be wrong. That is because the fundamental problem that the product mindset helps address is dealing with uncertainty.

The world is an incredibly uncertain place. And as you have seen about The Idea Maze and Deception you rarely know where things will end up even if you plan and execute well.

To be more product minded and to embrace the product mindset you need to be less certain about many of the things you take for granted in product management:

- Objectives (and OKRs)

- Goals

- Vision

- Strategy

- Customers

- Features and epics

- Backlogs

- User stories

- Story points, especially story points

This extends to less execution driven aspects of building:

- Opinions

- Product “taste” and “sense”

- “Two cents”

- Frameworks

- Methodologies

- Judgement

- Feedback

- Evaluation

- People

Most importantly, people. Part of my goal over the coming years is to do a better job of understanding why people are so certain and how to help them be more uncertain in helpful ways. This is why I’m doing the talk at the Product Led Festival on the product mindset. Why I’ve worked on a concept called Adversarial Product Management. And in my practice at work to question why you believe what you do.

How to be less certain?

If you believe the argument I’ve built above, the next question is how do you reject certainty of situations you find yourself in?

A key aspect of being less certain starts with the growth mindset. If you believe that you can continuously grow and change you can deal much better with uncertainty.

After adopting the growth mindset you will need to burn away your previous certainties. This is why becoming a great product person is so hard. You need to get rid of any training or schooling that has tried to create a sense of certainty in the world.

Others discuss these themes too. Barry O’Reilly has talked about the process of unlearning in the appropriately titled book "Unlearn: Let Go of Past Success to Achieve Extraordinary Results." Vaughn Tan has talked about how to adopt more open-ended styles to increase innovation in "The Uncertainty Mindset."

In my time working with product teams, I’ve found a few activities will help you get rid of undue certainty:

- Be more curious — rather than making confident statements, try to ask more questions. Especially about people. This includes your customers, coworkers, and everyone you know.

- Share uncertainty — share stories of times that things turned out differently than you thought they would. This is uncertainty! Hindsight is a great teacher of it.

- Practice it — through idk cards, case studies, decision-forcing games, and other simulation techniques you can start to build near-real experiences of states of uncertainty.

This is always a work in progress! There is always another set of assumptions you have that are no longer valid.

I want you to be less certain about everything you are working on. Certainty may feel good. Uncertainty may feel scary and uneasy. But there will always be some moment that the certainty will not be in service of what you are trying to do.

Embrace the product mindset, be more uncertain.

Hungry for more insights, advice, actionable learnings and thought-provoking content delivered by expert speakers? Catch Chris's presentation on the “The Product Mindset” and much more on-demand by becoming a PLA member. 👇

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn